Since the advent of the laser disc, with its better than broadcast quality image capabilities, the popularity of seeing wide screen movies in a letterbox format has continually gained in popularity with the public. The growing success of the DVD market further increases demand for the presentation of wide screen films just as they were seen in their theatrical runs.

In a large percentage of cases, the public are not being given what is claimed. So that they can help themselves in their buying decisions, many people turn to various video publications that offer "experts" that tell them in their reviews if the widescreen transfers are faithful to the original film. Those reviews are, unfortunately, more deceptive than the publicity that accompanies the video itself. Whether the deception is due to the need to fill space in a magazine or due to absolute and total ignorance is something we'll leave to you to decide. Here, we just present the facts so that you can be more aware of what happens in a video transfer and not put undue credence in what a magazine writer tells you.

Your favorite movie was shot in 70mm. Your favorite video magazine says the transfer is faulty because the aspect ratio is 2.21:1 instead of 2.05:1.

In the first indignity, the magazine is totally wrong about the typical 70mm aspect ratio. Let's clear that crap up right now, once and for all. 2.05:1 is not, and has never been the proper aspect ratio, for 70mm film.

This is a frame from an SMPTE RP91 70mm projector alignment film. This film is a very precision black and white print that is verified by the laboratory using microscopes to insure that it complies perfectly with design specifications, and it costs theatres an arm and a leg for a short length.

The film displays the recommended aperture dimension with the checkerboard pattern. If you want to measure the dimension of that pattern we'll save you the trouble; it's 2.21:1. Outside the checkerboard pattern we see the full camera aperture with its rounded corners. The area between the camera aperture and the extremities of the projector aperture is not intended for important information. Nothing in that area will be seen. The sides of the camera aperture will be covered with magnetic stripes. The top and bottom of the aperture are protected because negative splices would be visible if the full height of the camera aperture was to be used. The fine checkerboard pattern identifies the MAXIMUM amount of image that can be used on a motion picture screen. If your favorite video magazine is trying to tell you otherwise then write them a letter and give them the URL for this picture.

Your favorite video magazine recognizes that the proper aspect ratio is 2.21:1 for 70mm and says that your favorite film, transferred at 2.25:1, is very close to perfect.

Maybe your magazine is right and maybe it's wrong. We'll bet that they are wrong. An aspect ratio is a shape, not a guarantee of content, as is seen in here.

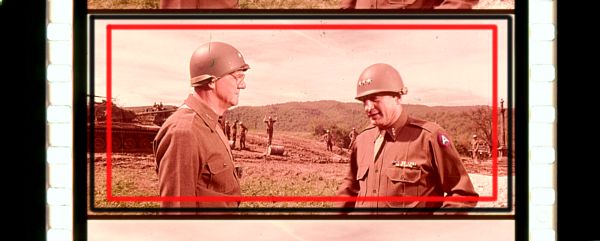

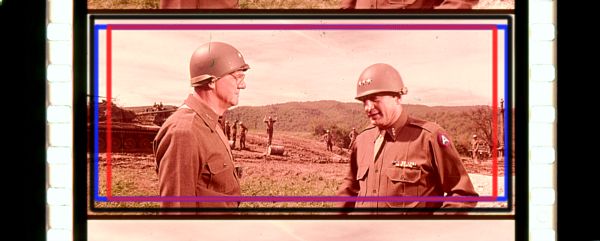

This letterbox video transfer of Patton measures out to an aspect ratio of 2.25:1, which is very, very close to its Dimension 150 70mm aspect ratio of 2.21:1. So does this qualify as being accurate? Only if you pay attention to numbers and not what's on the screen.

Here we see an actual frame from a Dimension 150 print of Patton. The black rectangular area inside the frame is the projector aperture as defined by the RP91 alignment film. The red rectangular area identifies the image that appears in the letterbox video transfer. They're close to the same shape, but there is an awful lot of image that didn't get put on the video.

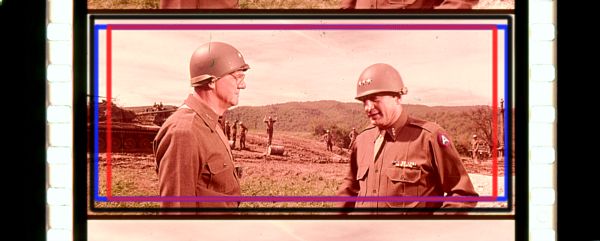

So it would appear that Fox Video is screwing the public. But appearances can be deceiving, and they certainly are in this case. In fact, it actually appears that they're doing the best they can to please the idiots at the magazines, even if it involves a little cheating. Here's the cheat: Few 70mm films are transferred to video from 65mm or 70mm elements. Typically a 35mm anamorphic reduction element is the source material. A slight amount of the total image width is lost in the conversion to 35mm and a somewhat greater amount of the vertical dimension is lost due to aspect ratio differences. The 35mm copy of the 70mm film will comply with conventional CinemaScope anamorphic dimensions. A closely cropped video transfer with an aspect ratio of about 2.4:1 would give the viewer about as much picture information as is actually available. But those video magazines keep telling us that if the film was done at 2.21:1 then the transfer should be the same. As a result, the video folks chop a bit off the sides of the 35mm image to bring the shape back to the point that the magazines won't bad mouth their transfer. It's stupid but those are the facts.

In the above frame the blue boundary identifies the MAXIMUM image area that can be duplicated from a 35mm reduction print. The image height is virtually identical to the Fox Video transfer, but cropping of the sides to appease aspect ratio purists loses approximately 10% of the total available width.

If you want to see a film projected in its correct aspect ratio then you have to see it in a theatre.

Don't make this assumption, especially in today's megaplex cinemas. Far too many theatres run all their films at the same screen size regardless of format. That's a cheap disservice to the viewer and to the producers of the film. But even the most self conscious theatres may find it necessary to show less than the maximum allowable image. Here's an example:

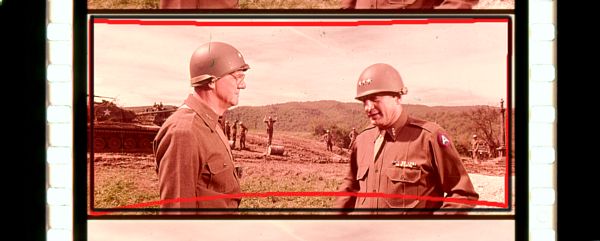

Shown here is our frame from Patton with the dimensions of a custom filed projector aperture plate shown in red. The sides of the aperture tilt outwards slightly to compensate for keystoning from the projection booth being built higher than the screen center line. The curve in the lower part of the picture that seems to consume so much of the image is necessary because the screen had a moderate curvature. While the aperture dimensions look odd when seen against the full frame, they create a properly masked image on the theatre screen, utilizing as much of the original film as can be shown in this particular theatre.

70mm projector aperture plate cut for curved screen with high projector angle, defined by red boundary in the photo above.

Courtesy of David Johnson

Put away your rulers and take the video magazines with a grain of salt. Perfection exists nowhere. If a film looks okay on your TV then don't worry about the aspect ratio. It is a sad fact that the video transfers of many of our old 1.37:1 films suffer from more cropping than the letterboxed films.

20th Century-Fox Home Entertainment has released a new transfer of Patton on DVD. This transfer features an extremely crisp, fully saturated image, and an aspect ratio of 2.35:1. This ratio, and the image content, represents the most faithful reproduction of the film frame that is possible from a 35mm reduction element.

Beeeutiful Image

Hats off to 20th Century-Fox Home Video. No nonsense, dynamite color and clarity, minimal compression artifacts, Oomph sound, exceptional supplemental materials. A fitting tribute to the entire production crew and cast of a beautifully made film.

Return To The Lobby

Return To The Entrance

E-mail the author

CLICK HERE

©1997 - 2000 The American WideScreen Museum

http://www.widescreenmuseum.com

Martin Hart, Curator